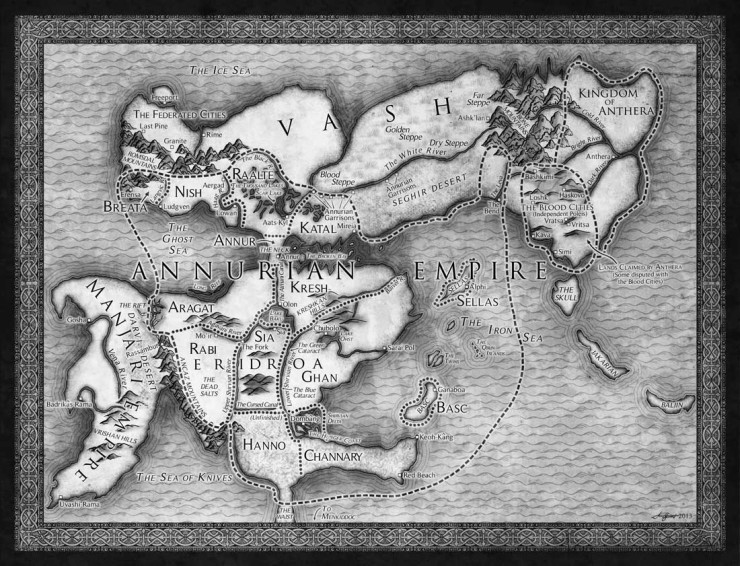

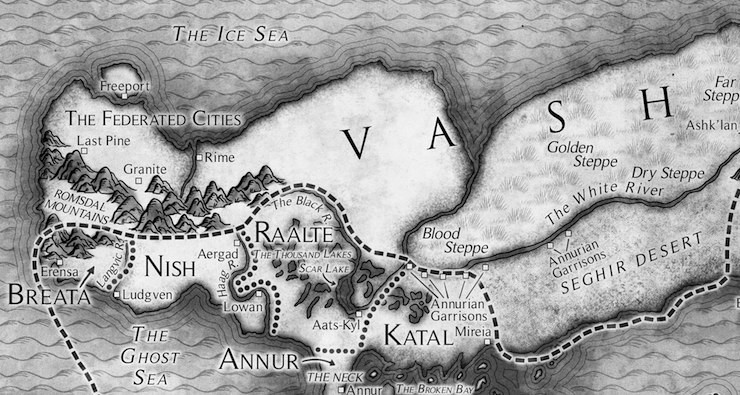

Sometimes I think I wrote three quarters of a million words of epic fantasy just so I could have my own damn map. In this, I am badly, deeply misunderstood by both my wife and my agent, neither of whom, I am certain, has so much as glanced at Isaac Stewart’s gorgeous map, despite the fact that it’s inside the cover of every damn book I’ve ever published. And I fear that they are not alone. I’ve come to realize that their ranks are legion, that there are literally millions of readers out there with no interest in maps, who will blithely skip past the most beautiful, crucial pages of a novel just to get to the actual words.

Cartographical philistines and longitudinal troglodytes, this post is for you.

A map is more than a two-dimensional catalogue of locations. First, and most importantly, it is a promise. By mapping a world, or a continent, or even a city, a writer assures his/her readers that their imagination has ranged well beyond the boundaries of their particular story, that they have imagined, not just the room in which the scene takes place, but the street beyond that room, the political structure responsible for building those streets and maintaining them, the agricultural system on which that political structure rests, the natural resources that undergird that system, and all the rest.

Every so often, I come across fantasy scenes that feel like a movie set. Everything looks good on the surface, but I can’t shake the nagging sense that it’s all just painted plywood over 2x4s, that if I looked behind those drapes or that door, I’d find, not an expansive land rich in history and mythology, but just a barren back lot and a bored gaffer on his smoke break. A map, a good map, at least, obviates that concern to some degree. It is a declaration of seriousness.

A map, like a sonnet, is also a challenge that a writer poses to themself. In part, the nature of this challenge comes from the strange pacing of the publishing industry itself. I was asked months ago, for instance, for the cover notes for my next book. What scenes, my editor wondered, might work well in the art? This was a tricky question, given that I hadn’t written any of the actual scenes. The exigencies of publishing, however, require this imagery early, and it’s the same with maps. Which means that a writer might well hand in a map for their story before that story is even finished.

While this might seem like an ass-backward way to do things, I love it. After all, stories—real and imagined—play out in a preexisting world. The world does not exist to serve the stories. I like working within the formal constraints of my own map when I write my books. I like looking at the terrain, the opportunities and dangers it presents, and then imagining my characters looking at that same map, trying to imagine what they would do, how they would move through that world.

Finally, maps provide a lens through which to view the events of the story. Every map, after all, contains the biases of the mapmaker, and while cartography might like to lay a claim to objectivity, there can be no objectivity in an artifact that excludes a thousand-fold the amount of information that it contains. Does a map contain political boundaries or landforms? What demographic information does it convey? Religion? Age? Ethnicity? What does it elide? What landforms are depicted? Which are excluded? Do those confident dotted lines obscure ongoing conflicts? No map can escape these deliberations, and even the most thoughtful cartography can’t offer the absolute truth, only a perspective on that truth. One reason I spend so much time studying a map before I read the book that follows is that I’m curious about that perspective. I get a glimpse before I even begin, into what the writer thinks is important about their own story.

Not that I expect any of this to sway my wife, who once drew a map of southern Vermont that was comprised entirely of a straight line joining three points: Putney, Brattleboro, Boston. Maybe, however, she’ll stop thinking I’m so deranged for spending so much time staring at the road atlas and ignoring Siri’s soothing voice.

This article was originally published March 24, 2016 on the Tor UK blog.

Map images by Isaac Stewart.

Brian Staveley‘s first book, The Emperor’s Blades—the start of his series, Chronicle of the Unhewn Throne—won the David Gemmell Morningstar Award, the Reddit Stabby for best debut, and scored semi-finalist spots in the Goodreads Choice Awards in two categories: epic fantasy and debut. The second book in the trilogy, The Providence of Fire, was also a Goodreads Choice semi-finalist. The concluding volume of the trilogy, The Last Mortal Bond, is available now from Tor Books. Brian lives on a steep dirt road in the mountains of southern Vermont, where he divides his time between fathering, writing, husbanding, splitting wood, skiing, and adventuring, not necessarily in that order. He can be found on Twitter at @brianstaveley, Facebook as brianstaveley, and Google+ as Brian Staveley or at his blog, On the Writing of Epic Fantasy.

I’ve always loved maps, real or fictional, so it’s nice to see others who share the sentiment. For as long as I can remember, I’ve had a preference for books that provided maps. I just received three of Mr. Staveley’s books as a gift and I look forward to jumping in.

I’ve also enjoyed seeing Isaac Stewart’s work in Brandon Sanderson’s novels.

Maps are why I always refuse to buy the Kindle version of fantasy books. The format absolutely butchers interior art, making the maps unreadable.

I like maps, but they don’t really transfer well to ebooks when you’re reading them on a phone.

Apparently on Kindles as well, per #2

To add insult to injury, Kindle skips the maps altogether when opening a book for the first time. I have to admit, this is my first time looking at the map. Tickled to see some of the city names. There are two blood cities that exist in real life in Bulgaria, the land of my birth – Haskovo and Vratsa. In fact, my mom was born in Vratsa (where her mom’s family is from; grandma took a road trip). Heh…

I do spend an extraordinary amount of time drawing maps in my head when reading books anyway… sometimes I’m wrong, sometimes I’m right. It’s always fun, though. I developed a love of maps at an early age. Back in the late 70’s I’d be the map keeper for our annual family trips from Sofia to a Black Sea resort South of Varna. It was always fascinating to find new roads with each new edition. Heck, I bought maps of Borneo and Sri Lanka as a kid just because I wanted to “see” them.

Count me among the map fans. I agree that they really enhance a story, since they hint at the richness of the worlds they depict; looking at them, I find they hint at the lives and stories that may be going on beyond the actual story I’m reading.

I suspect like a lot of people here, a love of maps came from early favorites: Mr. Shepherd’s (and Christopher Robin’s) map of the Hundred Acre Wood in WINNIE THE POOH, Jules Feiffer’s map of the Lands Beyond in THE PHANTOM TOLLBOOTH, and the maps in Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain novels (in a nice touch, these latter “evolve” from book to book, as new places are visited and old places are changed or destroyed).

A problem with maps at the front of the book is that they lack context. When I first open a book, it’s hard to tell what parts of the map are important; or to remember the information the map provides. They can be cool to flip back to though and they can be really good for re-reads.

So why is that science-fiction stories almost never have maps?

As an author with a propensity for drawing maps of the entire planet my stories take place on, this makes me feel a lot better. I’m glad I’m not the only one who thinks a map is crucial to a fantasy story, that it provides insight into the world far beyond what actually makes it into the finished work; they’re also almost always beautifully illustrated, which makes studying them worth it in and of itself. I usually get kinda disappointed whenever an author chooses not to include a map for much the same reason as you, Brian: it feels too much like they’re constructing a set piece for a scene and making up the setting as they go along.

The best things about maps are: they convey a sense of scale, and a sense of connection between various parts of the story. I remember seeing some maps when I was a kid, of the area my family was living in, and not only getting a sense of connection – “so this place, which I’ve never been to, is not that far from this mighty river, which I have been to, and my own little river flows into it. Adn then there’s its mouth …” but also getting a sense of the scale of the whole area – “so it’s two days walking to such-and-such if it’s half-a-day walking to so-and-so!?!”

I would’ve have a much harder time making sense of Patricia Wrightson‘s The Nargun and the Stars if it hadn’t had a map of the property in the front, where I could get a picture of where what happened when.

As mentioned upstream, Kindles really don’t do maps well. Epic fantasy still comes off better on paper, when I can open up that big book and pour over the world depicted therein.

Originally I would pore over maps located at the front of books, but now I give them little more than a cursory glance and only refer to them if the story requires me to. Which I don’t believe it ever should, if it’s written well. I appreciate the added layer of magical escapism they imply, but it’s become lumped into the same category as the cover by which you should never judge a book.

I am a cartographer, maps are my life. I pour over every map I see and love the maps in the books I read. They give me a sense of time and place, a sense of reality, if only for the story within.

@6 Another problem with maps at the front of the book–that is, printed on the inside of the front or back cover and first/last pages–is with library copies. Too often the dust jacked is glued or taped over the map and/or the card pocket or bar-code for checkout is also stuck on it.

I gotta admit, one of the easiest ways for me to get distracted from working on my current novel is to start drawing a new map. A “quick sketch” has a way of turning into hours of meticulous detail, because you just KNOW that river doesn’t go “here” — it goes “there” :p

Yup. Maps. That’s ( those are ) the ticket. How in the heck are you going to stay oriented if you have no map. Tolkein and Lewis did it. Time Bandits brought theirs with them. I wouldn’t venture into an adventure book that didn’t have at least a rudimentary chart of ‘You are here’ and ‘There be dragons here’, if for no other reason than to avoid being eaten for the first couple chapters until I got my bearings. Too, as an author, it helps keep one oriented, holds one accountable to one’s world-building, and provides copious fodder for new characters and plot inflow. I, for one, am a fan. A major league fan.

I appreciate fantasy book maps, but don’t ever use them. Unless I decide to set a game in that world, of course, but that hasn’t happened in about 10 years.

Bonus: if you want to have fun, run a fantasy map past an actual geographer.

I love including maps in books. I often draw maps, and then decide to write a novel about them. I believe maps are vital to any fantasy novel.

Regarding the poor quality of maps on the Kindle: I read on the Kindle but if there are maps or other pictures/illustrations, I will open the book on the Kindle Fire to look at them. You could do this with the Kindle app for other tablets. Not as easy as being able to flip back to a map, but it works and I love reading on the Kindle.

@18 Having the maps open on another device would actually be convenient for cross-checking. Flipping to the front is annoying enough in hardcopy books that I only do it when I’m really confused. Though it depends on having the extra screen available.

maps make it real! good editorial!

I do love maps, and not just fantasy maps. Quinn Yarbro’s series on St.-Germaine books are set in different historical times and so the maps are interesting from a modern perspective. And Rosemary Kirstein’s series The Steerswoman, who roam the world seeking knowledge, has maps that get more detailed and precise as the series progresses.

A fantasy novel isn’t a real fantasy novel if it doesn’t have a map. Well, Glen Cook’s Black Company novels being the only exception I can recall right this second.

Maps are great. Almost every time.

The only time they are annoying is when the map drives the action, and the author can’t help themselves, eling obliged to send the characters across the face of the earth for the simple purpose of enabling the writer to demonstrate the amount of worldbuilding.

(I’m looking at you, Eddings!)

Travel is fine, so long as it is demanded by the plot. Not the map.

That last sentence killed me! I really do miss my mid 20’s when map book rather than smartphone navigation was the norm. For one thing all the street names are shown, unlike with a phone, where consistently the only street name NOT shown is the one you want!

Anyway, I’m also glad that fantasy map appreciation is strong. I write my stories like that, often looking to the map for inspiration, not to mention keeping journey times consistent and properly paced over rough vs smooth terrain. Even if the book is never published (travesty), and even if the map is never included (bigger travesty), I’ll know the story is better for its existence.

Also, I’ve made it beautiful FOR you, dear reader! I give you art; love it, you goddamn philistine!

One more thing. I recently carved a globe out of stone, and my greatest joy in that process was not so much the carving itself but the intimate and meticulous navigation of Earth’s rivers and coastlines, faithfully reproducing them in stone, and all the while discovering not simply the broad strokes of each country and continent but every twist and curve, every particular shape suddenly proved different from what I thought I knew. People don’t live in Africa, or Asia, or America, we still exist in the small spaces, within communities and specific geographies, and I think that was what I was reminding myself of. Yes, along with holding the globe in ones hand comes that feeling of global interconnectedness which astronauts speak of, but really looking down at the detail is how we come full circle in our understanding of ourselves.

As a writer of fantasy stories, I depend on the maps I make plus it’s fun making new worlds. I also enjoy looking at maps in fantasy novels and if I buy a kindle ebook, I look at the map on myiPad kindle app to see it clearly.

Fantasy works can often be judged quite accurately without reading a word of their prose by simply look at their maps with a critical eye. Is the geography realistic and consistent with the way geographic features develop in the real world? Do political boundaries follow defensible natural borders such as rivers or mountain ranges? Are place names within a culture consistently and convincingly named? Is the map dense with texture and nuanced world-building, or is it a too-thinly disguised plot point diagram? Fantasy works often need maps, just to make the whole reading and immersion process tractable :), but they need to be done well since they are usually the first things readers see (and predispose themselves by). Good essay, and this topic should get much more attention in the fantasy writing community.